FPC LEVERAGE RATIO REVIEW

RESPONSE FROM THE BUILDING SOCIETIES ASSOCIATION

The Building Societies Association (BSA) is pleased to respond to the Financial Policy Committee’s review of the leverage ratio. The BSA represents all 44 UK building societies. Building societies have total assets of over £325 billion and, together with their subsidiaries, hold residential mortgages of over £240 billion, 19% of the total outstanding in the UK. They hold nearly £240 billion of retail deposits, accounting for 19% of all such deposits in the UK. Building societies account for about 28% of all cash ISA balances. They employ approximately 39,000 full and part-time staff and operate through approximately 1,600 branches.

General remarks

The BSA continues to support a suitably differentiated leverage ratio framework, as clearly envisaged by Article 511 of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), as a supplementary tool to the risk-based capital framework of CRR, which should remain the primary regime. The Capital Measure must remain total Tier 1, as already specified in CRR Article 429.

Reasoned contributions to the debate on use of a leverage ratio, that will lead up to its likely adoption into EU legislation as a Pillar 1 requirement, following the process laid down in CRR Article 511, are to be welcomed. But the FPC leverage framework marks a fundamental departure, even from what has so far been agreed and published by Basel or in the EU, and – in effect – abandons the primacy of risk-based capital adequacy in favour of a more primitive approach, as an over-reaction to the problem of model risk. In short, we regret the FPC appears to have come up with the wrong answer.

The Bank itself took a wiser approach back in 1980, with its ground-breaking paper The Measurement of Capital, using a form of leverage, or gearing, ratio as a supplementary tool to the primary risk based measure. At that time the Bank said:[1]

“…..the risk measure of capital adequacy should take precedence. But the gearing measurement will have a place in ensuring that an institution is not running ahead of its probable capacity to sustain its business in normal circumstances.”

Moreover, the FPC’s proposals understate their damage to low-risk business models, and thereby to the necessary diversity of the banking sector, and make no attempt to differentiate by business model – the only gesture being a systemic add-on. In fact, the leverage ratio framework has the potential to become the primary capital constraint for building societies and other mortgage lenders, rather than a complement as the FPC intends. This discriminates against their business models, implicitly favouring the universal banking model, and would create the various perverse incentives the BSA has already pointed out to the FPC Secretariat and which are recognised in the interim report. Consequential diversification into higher-risk assets – moving up the risk curve beyond their natural risk appetite – is not, in general, a sensible response by societies, and is regularly criticised by the PRA whenever suggested or detected.

Finally, the FPC proposals as they stand do not adequately address some key issues raised by the Chancellor in November, and in particular they do not justify a departure from international or EU timetables and definitions. They appear to add complexity in order to guard against problems that various other regulatory reforms have already been introduced to address.

The BSA does not therefore support :

* the full framework of leverage requirements proposed by the FPC, which are clearly no longer a supplementary tool, but instead a parallel and duplicative regime, adding unnecessary complexity;

* the absence of any differentiation in the base requirement (contrary to the steer in CRR Article 511), which discriminates indirectly against building societies and creates the risk of consequential diversification by low-risk firms beyond their natural risk appetite;

* moving the Capital Measure to predominantly CET1, with a small proportion of AT1 for the base requirement, when both Basel 3 and CRR (Article 429) unambiguously establish (total) Tier 1 as the Capital Measure for the actual leverage ratio calculation (required to be published from 2015). High level triggers (typically 7%, well above the 5.125% CRR minimum) will ensure that actual AT1 issues possess ample loss absorbency – so there is no need for separate, cross-cutting constraints on the contribution of AT1 to regulatory capital beyond those already in place under Basel 3/ CRR;

* implementing any further leverage measures in the UK going beyond what is required already under CRR and CRD (and the PRA’s 2013 leverage ratio exercise on the eight largest UK banks and building societies) ahead of the EU legislation called for under Article 511 (or until it is evident that such legislation will either not be agreed, or will no longer apply to the UK). The FPC paper makes no evidence-based case that such anticipation is necessary.

* reaching conclusions regarding alternatives to the leverage ratio until policy makers decide how both the leverage ratio, and certain alternative tools, would be calibrated, and therefore the relative impact / influence of the alternatives.

Responses to questions in the Leverage Ratio Review Interim Report

Question 1 Do you agree that the leverage ratio plays a complementary role to risk-weighted ratios and stress tests in assessing capital?

The leverage ratio (LR) should be a supplementary, or ancillary, tool, not a parallel framework of requirements. We support the use of a leverage ratio as a cross-check for risk-weighted capital, supplemented by judgement. Andrew Bailey indicated such a role for the leverage ratio in a recent speech, referring to it as “a very useful check and balance and it should prompt searching questions about the danger of model errors in more complex capital assessments”[2]. However, a high minimum leverage ratio would become the primary driver of capital requirements for firms focussed on low risk assets, rather than a complementary, let alone supplementary, regime. The leverage ratio becoming the primary driver is not satisfactory, as it incentivises firms to take on more risk, pass on higher funding costs to consumers and/or reduce stocks of low risk assets. Furthermore, as is acknowledged in the report, some banks that failed in the financial crisis were not highly leveraged.

The FPC’s interim report does recognise the impact of a leverage ratio will be greater on firms with low average risk weights, but the report also asserts that this is consistent with the objectives of the leverage ratio as a firm with low average risk weights would be particularly susceptible to small errors in models or to unexpected shocks. But to give too much weight to a single leverage ratio implies that the FPC does not recognise that there is any reliable estimation of differences in riskiness across asset classes and firms of varying size, scope or complexity and disregards all past performance and the extent of any security. This disregard is an over-reaction to the risk of modelling errors.

The European consensus, recently enunciated by the European Commission, is that the LR is designed to cover the risk of excessive leverage, and be a backstop to risk-sensitive capital requirements. Hence the LR is neither designed, nor should be calibrated, as an overall leading capital requirement that may lead to moving away from low risk (weighted) business and possibly leading to improper pricing of risks in loans and other financial products.

We support the simple approach proposed in Europe to use a differentiated leverage ratio that accepts that the degree of model risk and exposure to unforeseen events are lower for some business models.

Question 2 Do you agree with the considerations regarding potential alternatives to the leverage ratio?

The role of a leverage ratio within a capital framework is to guard against risks arising from modelling errors and seemingly extreme events. However, the FPC’s proposed leverage ratio framework is an overly complex way to address model risk relative to a simple ratio combined with various other reforms that have been introduced and developed since the financial crisis.

Regular supervisory assessments via Pillar 2 reviews can help to reduce model risk, alongside stress tests of mortgage books, as well as internal audits of IRB approaches, and indeed audits of risk-based capital requirements generally. Under the revised Pillar 2 framework, using Pillar 2A to ensure firms hold capital for model risk could be a preferable, and more targeted, approach. A risk weight floor may also be a more targeted way of dealing with model risk but without knowing at what level a floor will be set it is impossible to assess its appropriateness and impact relative to other tools that have been proposed to address the same perceived issue. Furthermore, as the FPC has already been granted powers of direction over sectoral capital requirements, it currently has the authority to require higher capital requirements for specific assets. In effect, it can already address specific concerns about the modelling of capital requirements for certain types of assets.

Finally, the EBA’s forthcoming portfolio benchmarking exercises are potentially a better way of ensuring that capital requirements calculated using internal approaches do not systematically and significantly underestimate capital requirements and will also assist understanding and comparison of internal risk weights.

The FPC notes that another benefit of a leverage ratio is that it can limit the extent to which risk based capital ratios are driven down during benign conditions. However, part of the rationale for the counter-cyclical buffer under the risk weighted framework is precisely to address the risk that models are becoming lax through the cycle, so an excessive leverage ratio framework aiming to address the same problem would overlap and duplicate this buffer, potentially resulting in inefficient levels of capital.

Question 3 Do you agree with the advantages and disadvantages of symmetry between the leverage ratio framework and the risk-weighted ratio? In particular as they relate to:

• including a minimum requirement and buffers analogous to the risk-weighted framework;

• establishing a leverage conservation buffer in proportion to the risk-weighted buffer;

• eligible capital;

• the level of application; and

• the scope of firms to which the framework is applied.

We do not agree with erecting a parallel leverage regime that undermines the primacy of risk based capital adequacy, and regard the search for full “symmetry” as misconceived.

The benefit of a leverage ratio comes in large part from its simplicity. The FPC’s proposal for a framework of a minimum and various buffer leverage ratios, and the potentially complex interactions with the risk weighted framework, reduces this valuable simplicity. Recent research published by the Bank supports the view that simple approaches can support more complex approaches in the presence of uncertainty.[3] Simple approaches that are easy for stakeholders to compare are also found to have benefits, so if the UK were to implement its own complex framework ahead of international agreements, it may be counterproductive:

“While an area for future analysis, the extension of these ideas to the macroprudential sphere may have important implications for both the design of instruments and macroprudential risk assessment. In particular, it speaks to the use of simple instruments for macroprudential purposes. And it suggests using simple, high-level indicators to complement more complex metrics and other sources of information for assessing macroprudential risks (Aikman, Haldane and Kapadia (2013); Bank of England (2014)). More generally, simplicity in macroprudential policy may also facilitate transparency, communicability and accountability, thus potentially leading to a greater understanding of the intent of policy actions, which could help reinforce the signalling channel of such policies.”

The proposed leverage ratio framework, matching the structure of the risk weighted framework, would add to the complexity facing suppliers of capital as it is not clear when any of the various buffers and minimums would bind, and thereby when distributions may be restricted. Under stress, the leverage ratio will not react in the same way as risk weighted assets because RWAs have inherent procyclicality whereas LR exposures are relatively invariant.

We oppose strongly the eccentric move to predominantly CET1 as the capital measure. Limiting to 25% of Tier 1 the use of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) is inconsistent with Basel III, CRR (Article 429) and the common definition of the leverage ratio endorsed by the Basel Committee and the EU for LR disclosures from 1 January 2015. Moreover, even if the principle of symmetry is accepted as being a valid basis on which to develop the regime, the proposal is not symmetrical. This is because the risk-based regime comprises both going concern (Tier 1) and gone concern (Tier 2) capital and minimum requirements are given by reference to total capital (8%), of which 4.5% must be met by CET1. This gives a CET1:AT1 ratio of 56:44 instead of the 75:25 or indeed 100:00 options in the consultation paper. For the FPC to justify this unilateral move by appealing to symmetry with the CRDIV/CRR risk weighted regime is wholly unsatisfactory when this symmetry has not been applied under CRR itself.

The above points suggest to us that it would be better to wait until both the FPC has determined its medium term priorities on the capital framework and the final decisions on the leverage ratio have been made in Europe, rather than pre-empting decisions there only to have to amend or repeal part or the whole of the UK’s framework, and in the meantime creating confusion as firms begin to report actual LRs under CRR.

Question 4 What are your views on the remaining design elements discussed in Chapter 3, in particular regarding the interaction between Pillar 2 and the

leverage ratio, including for pension risks, and transitional arrangements, including coverage of only the large UK banks and building societies?

As the PRA has already introduced a minimum leverage ratio for the largest UK banks and building societies, we see no reason to develop that further ahead of EU legislation, either by expansion to other firms, or by imposing on the large institutions the more elaborate framework proposed by the FPC.

In the unlikely event that the FPC can make a convincing evidence-based case in its final report for the UK to press ahead unilaterally with its own leverage framework, it would be least disproportionate to focus this on the major banks and building societies in the first instance, rather than applying it to all firms subject to CRD IV/CRR.

Notwithstanding this, firms should be allowed sufficient time to transition to a new regime. Recent experience of implementing the CRR involved the PRA accelerating towards end-point treatment from Day One, having previously signalled the opposite. If the PRA is expected in short order to take steps to respond to the FPC’s direction firms, in turn, will inevitably make decisions and plans affecting their business models and risk appetite in haste.

Question 5 What are your views on the impact on different business models of a ‘baseline’ requirement in steady state?

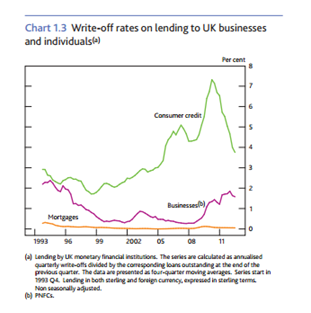

The FPC says that which of the risk weighted and leverage ratios binds, and when, will depend on the types of risks to which an institution is exposed. For firms that concentrate on low risk assets the leverage ratio could, de facto, become the sole driver of capital requirements rather than being complementary to the risk weighted approach. As the FPC notes, relying on a minimum leverage ratio alone would ignore significant aspects of the risks firms face. This is despite long runs of data indicating that mortgages have exhibited lower losses than other types of lending, as shown in the chart below. (Source: Bank of England, Trends in Lending, June 2013)

As the BSA has consistently argued, any minimum LR should be differentiated, in line with the steer contained in Article 511. The original proposals from the European Parliament would provide a good point of departure. The importance of appropriately catering for the diversity of prudent business models is well expressed in CRR Recital 115 :

“In order to take account of the diversity of business models of institutions within the internal market certain long term structural requirements such as [the NSFR and] the leverage ratio should be examined closely with a view of promoting a variety of sound banking structures which have been and should continue to be of service to the Union’s economy.”

Also missing from the FPC’s prescriptions is the vital ingredient called for in CRR Recital 95 :

“Based on appropriate analysis and also taking into account historical data or stress scenarios, there should be an assessment of the appropriate levels of the leverage ratio that safeguard the resilience of the respective business models….”

The FPC is also right to consider how the transition to a high minimum leverage ratio would come about in practice. The FPC recognises that some building societies build up voluntary buffers because they might find it more difficult to raise external capital than banks, and claims that their resulting current low levels of leverage mean that they may not be affected by the introduction of a minimum leverage requirement and conservation buffer. However, the boards of directors at these societies may seek (and indeed be encouraged in this by the PRA) to maintain their voluntary buffers over and above the leverage buffers, rather than being satisfied that their voluntary buffer and other leverage buffers can overlap. Official buffers of any kind tend to become additional requirements.

And as the interim report acknowledges, although Nationwide Building Society has successfully issued the CET1 instrument Core Capital Deferred Shares (CCDS), it is not currently clear that this option is yet open to smaller building societies on a commercially viable basis.

Question 6 Do you agree with the considerations regarding a supplementary leverage ratio component for G-SIBs and RFBs?

The principle that G-SIBs and D-SIBs have to hold more capital is already established under CRDIV – but it is not clear that also having systemic add-ons for the LR adds enough value.

Question 7 Do you agree that it would be desirable to scale up the leverage ratio in proportion to the supplementary risk-weighted buffer for G-SIBs and

RFBs, with a presumption of symmetry?

As we do not in general support the “parallel regime” approach to leverage, or the symmetry argument, again we question whether this adds value.

Question 8 Do you agree with the desirability of being able to vary the leverage ratio requirement in the same way as risk-weighted requirements can be varied

through the countercyclical buffer?

No. We do not support the elaboration of a parallel regime including multiple buffers around what was supposed to be a simple supplementary tool. And as explained above, risk weighted assets have inherent procyclicality, while leverage exposures by comparison are relatively invariant.

The FPC will get powers of direction over a time-varying leverage ratio in 2018, as has been agreed by the Government. The interim report does not justify why obtaining these powers ahead of this date is necessary.

If a time varying leverage ratio is implemented and applied, firms must be given ample time to adapt to higher requirements. Under CRD, firms needing to comply with the risk weighted countercyclical buffer will have at least 12 months – the same minimum should apply to any variable leverage ratio. The greater the capital shortfall and the shorter the timeframe to meet the higher minimum, the more likely that the transition will be made by reducing lending to households and businesses rather than by raising new capital. It is also important that any countercyclical leverage buffer (if implemented), as with the risk weighted CCB, is reduced in a symmetrical manner in the “risk-off” phase of the cycle rather than being used to ratchet up capital requirements over time.

Question 9 Do you agree that, as a guiding principle, the leverage ratio should vary in proportion to the risk-weighted countercyclical buffer?

No. See above. Also, the stated aim of this proposal is to reduce model risk, i.e. the risk of inaccuracy that may be inherent in a calculation of risk-weighted assets. This makes varying the ratio in proportion to risk-weighted assets, in which there may only be a modicum of confidence, both circular and counter-intuitive.

Question 10 Do you have any views on the cost-benefit analysis considerations

While we recognise that this is an interim report, we believe that the FPC has a long uphill distance to go in its final report to make the evidence-based case that the Chancellor requires before implementing a leverage ratio ahead of the international timetable or at a higher level than the international standard. At this stage, the case is simply not made.

The interim report notes that determination of the appropriate numerical value is outside the scope of the leverage review. However, doing a CBA on the proposed structure of the leverage framework alone is likely to be partial and may substantially understate the ultimate impact of the leverage ratio framework. If the calibration of the leverage framework results in a high minimum this could easily outweigh the costs of the proposed leverage framework relative to a simple regime. The Governor of the Bank of England has committed to provide a draft Policy Statement to Parliament in early 2015, so the Bank will clearly have developed its thinking on the calibration by the time of the final report. It should therefore use some indicative figures, or various possible scenarios, in its cost-benefit analysis, and set out how firms are expected to transition from current situation to desired end point.

It is important that the cost-benefit analysis is not merely a theoretical exercise based on aggregate figures or a representative bank. The Bank and PRA already have a vast array of data on firms’ current and forecast capital positions. Even if the analysis is not published at a firm level due to its sensitive nature, the FPC needs to consider how, in practice, different firms are expected to transition from current capital positions to a reasonable expectation of the leverage regime and levels, and over what timescale.

The cost-benefit analysis also needs to assess the incremental benefit of the FPC’s proposals on top of regulatory reforms and policies that have been or are due to be introduced, rather than against some theoretical base case that does not reflect the current regulatory environment including the CRDIV/CRR risk based capital requirements framework, sectoral capital requirements, the EBA portfolio benchmarking exercise, and so on.

The final report also needs to set out the impact of the proposed framework on the ability of the banks, building societies and other firms to support growth in lending to consumers and businesses, and what this means for the diversity of provision. Previous FPC recommendations for higher capital requirements at large banks and building societies have required them to set out to plans to raise capital on the condition that they do not reduce lending, but the cost benefit analysis should consider that there comes a point when issuing new capital becomes prohibitively expensive.

The FPC’s final report on the Leverage Ratio Review should give opportunity for a further round of consultation with interested parties so that practical issues can be fully explored in advance of the draft Policy Statement being made available to Parliament.

[1] The Measurement of Capital, paragraph 8 (5 September 1980).

[2] “The capital adequacy of banks: today’s issues and what we have learned from the past” Speech by Andrew Bailey, 10 July 2014 http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2014/speech745.pdf

[3] Taking uncertainty seriously: simplicity versus complexity in financial regulation, Bank of England and Max Planck Institute, May 2014

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Documents/fspapers/fs_paper28.pdf